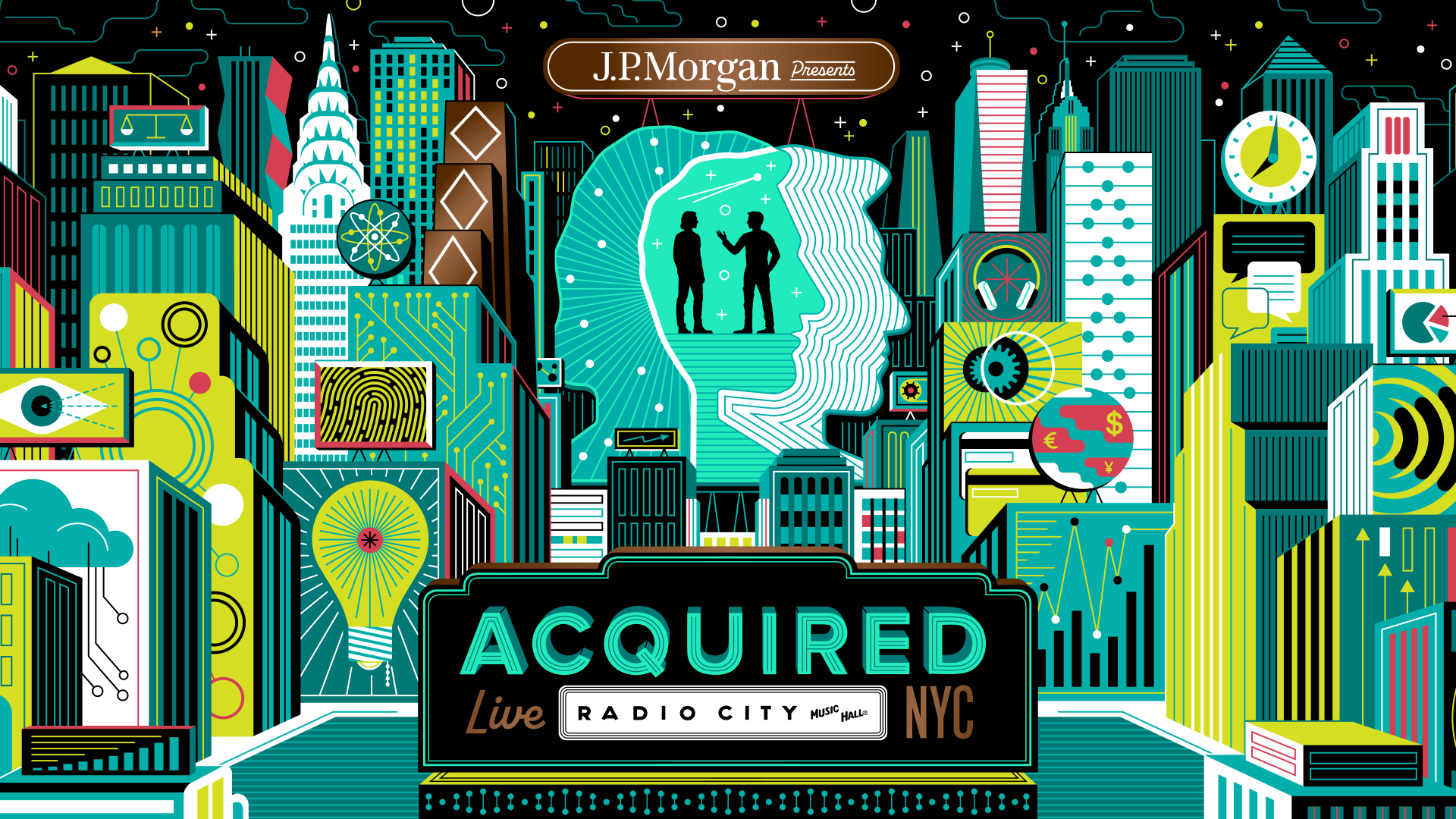

Acquired Live at Radio City Music Hall (Presented by J.P. Morgan)

ACQ2 Episode

It’s finally here! Today we are releasing Acquired’s first “concert film” — the full video recording of our Radio City live show from this summer with Jamie Dimon, Andrew Ross Sorkin, New York Times CEO Meredith Kopit Levien, Barry Diller, and cameos from around the Acquired Cinematic Universe including Christina Cacioppo, Ben Clymer, and Howard Schultz.

To watch the full production on any device, please head over to Spotify where you’ll find it available for free in the Acquired feed right alongside all our other episodes.

Sponsors:

- Live Show Presented By: J.P. Morgan

- Shopify

- ServiceNow

More Acquired:

- Get email updates and vote on future episodes!

- Join the Slack

- Subscribe to ACQ2

- Check out the latest swag in the ACQ Merch Store!

Sponsors:

- Rippling: https://bit.ly/acquiredrippling

- Statsig: https://bit.ly/acquiredstatsig25

- Odd Lots: https://bit.ly/acquiredoddlots

- ServiceNow: https://bit.ly/acquiredsn

Sponsors:

More Acquired:

- Get email updates with hints on next episode and follow-ups from recent episodes

- Join the Slack

- Subscribe to ACQ2

- Check out the latest swag in the ACQ Merch Store!

Oops! Something went wrong while submitting the form

Transcript: (disclaimer: may contain unintentionally confusing, inaccurate and/or amusing transcription errors)

I can't believe the show sold out without us telling anyone what's happening.

I know, right?

I hope.

I hope people aren't disappointed.

Should we have told them at least one guest, or released a detail?

I like it. It's Broadway. It's theater. You're in for a show.

Come see.

Acquired is a show.

Yep. The suspense, the mystery. Which train are we taking again?

I think it's the B.

B, B. Nice.

New York really does feel like the center of everything.

You know the famous New Yorker cartoon about how New Yorkers see the geography of America? No, it's the island of Manhattan in the cartoon, and then there's the Hudson River, and then there's just California on the other side of the Hudson River. There's nothing in between.

We've got a little bit of time before the show. What do you think about a hot dog?

I'll get a hot dog.

All right, let's do it.

Thank you.

It is my favorite thing to do when I come to New York.

It's the best.

Spend some time in Central Park, walk around all day, pop out, get bagels. I was trying to think: what was the first Listener Live thing we ever did?

I think it was the GeekWire conference in Seattle. And then we did the WeWork in San Francisco, in the Tenderloin.

It was about 100 people.

Yep. The PA system went out halfway through.

Someone ran to Best Buy.

Yep. Picked up a new PA system. That was amazing. We've come a long way.

We've come a long way.

Should we do it?

Let's do it.

New York City! Please put your hands together for Ben Gilbert and David Rosenthal. Who got the truth?

Is it you?

Is it you?

Is it you? Who got the truth now? Is it you?

Is it you? Is it you? Hello, Acquired listeners! We are so, so excited to have you all here tonight for our live podcast episode recording. So, all right, David, should we do it?

Let's do it. I think this was better in theory. I'm not sure. It feels like kind of a waste of all this: this stage, this Radio City Music Hall that we have here.

I think you're right. Should we do the other thing?

Yeah, maybe we should do the other thing instead. Let's do that. Hey, Mike, could you help us level it up a little bit in here? I think we can cook something up.

Radio City! Are you ready? Who got the truth?

Is it you?

Is it you? Is it? Who got the truth now? Now?

Is it you?

Is it you? Is it you? Set me down, say it straight. Another story on the way.

Who got the truth?

Who got the truth?

Radio City! Mike Taylor, everyone! Woo! Now, this feels a little more Radio City.

Yes, it does. David Rosenthal, you look sharp.

You do too, Ben.

I suppose we have our friends at Hermès to thank for helping us celebrate the occasion and show up in style as always. As always.

Indeed.

Indeed. Well, welcome to Acquired Live at Radio City Music Hall. Thank you so much to all of you for coming out, and those of you who traveled from far away. We've got people from different states, different continents. Thank you so much.

So, what are we really doing tonight?

Ben and I thought long and hard about what to do tonight. What is the best show we can put on on the greatest stage in the greatest city in the entire world here in New York?

Woo!

And we realized that what we should do tonight is obvious what Acquired should do. We are going to have three conversations with three of the city's most iconic company CEOs.

The way we're going to do it is in two acts. So, Act One, we've got a big conversation with an important American company that we haven't covered yet here on Acquired. We're going to tell that here with the protagonist himself. And in Act Two, after intermission, we are going to have some fun, and we're going to try out a new format for Acquired, specifically tailored for Radio City Music Hall.

Yep. So, for our first conversation, there is really only one active CEO today here in America who transcends leading his company and really is also looked to as a leader for our country.

His company is now worth around $800 billion, and not only is it the most valuable company in New York, but it's the most valuable company east of the Mississippi.

So for tonight's big conversation, please welcome the Chairman and CEO of JPMorgan Chase, Jamie Dimon. Jamie, it's great to have you here.

Well, this feels appropriate.

You guys dressed up for me.

You dressed up for us, too. Thank you.

Well, we know you're a big history buff, and we consider ourselves historians above all else. So what we'd like to do here tonight is walk through the 20-year story with you of how you turned JPMorgan Chase from a bank among many to the most systemically important financial institution in the world. Are you game?

Sounds great. Thank you.

We want to start in 1998. You and your mentor, Sandy Weill, have just spent the past 13 years building the modern financial institution, a conglomerate, really the blueprint for what JPMorgan Chase is today. Except it's not JPMorgan; it's Citigroup. And everybody on Wall Street in the entire world expects that you are going to be named CEO of Citigroup in short order.

This is 1998.

1998. This is not what happens. Instead, you get fired, and you have to restart your whole career, everything, your whole life, from scratch.

Sorry to start here, by the way.

Before we get into what you do next, what was the model that you and Sandy built at Citigroup?

Okay, first of all, I am thrilled to be here. I want to congratulate these guys for building Acquired. It's a great, intelligent addition to what we need to learn in society.

And so, I would say it wasn't quite the model, because if you look at what we did at Commercial Credit, Primerica, which then Travelers, and merged, we were a financial conglomerate. We bought lots of companies and lots of different businesses. We fixed them up, we turned around, we made money. And then we merged it with Citibank, which obviously was a huge bank. And, my view was, we should skinny it down and kind of shed the parts that aren't as important to the rest of the company and keep the things that strategically belong together. It was one of my small disagreements with Sandy about the future of the company. And so. But it was big. It was making a lot of money. It was quite successful at the time. And then I got fired.

So, how are you feeling in that moment?

When I got fired?

Yeah, that moment.

Well, my wife is here, and I was hosting 100 people recruiting kids in my apartment in New York City, same apartment I have now. And they called me. We had a meeting a Sunday at 4:00 p.m. that night. And Sandy and John Reed called me up and said, "Can you come a little early? We got a bunch of stuff to talk about."

I was the President, Chief Operating Officer. I said, "I can't." They said, "Well, it's really important." So I drove up there and I sat down in the room with Sandy and John, and they said they wanted to make a few changes, and they had three of them.

And they said, "One, we want to make this person in charge of that." I said, "Okay." Well, that didn't make sense to me.

The second one, they wanted to make someone in charge of the global investment bank, which I was running. I thought it was another stupid decision.

And the third is, they said, "We want you to resign." And I said, "Okay." Because, at that moment, I knew it was all arranged. The boards had voted, the press release was written, the management team was coming up. So I waited for the management team to come up. I wished them the best. I said, "You guys have a chance to build one of the great companies." They all thanked me.

Sandy said, "You want to do the press with me?" I said, "Yeah, but I'll do it from home." So I went home, went to see my kids. One of my daughters is here too. They were like 12, 14, 12, and 10. And I walk in the front door and tell them I was fired. And the youngest one says, "Daddy, do we have to sleep on the streets?" I said, "No, no, we're okay." And the middle one, who's always obsessed with college for some reason, "Can I still go to college?" I said, "Yeah." And the one who was here, the oldest one, said, "Great, since you don't need it, can I have your cell phone?"

And then that night, about 50 people came over. All the same people I just met, all the management team, bringing whiskey. And it was like being in your own wake. And there's one really tall guy who came in, a very good friend of mine. And he looks. And my daughter looks up and says, "Who are you?" He says, "I work for your daddy." And she says, "Not anymore you don't." That was it. I was okay. I tell people my net worth, not my self-worth, was involved.

And for anyone who doesn't already know Jamie's story, you were the rising star. I mean, you were. Citi was the biggest bank. You were the heir apparent. This was unfathomable. And for you to take it this gracefully, it says a lot. So you're wandering in the woods, as best I can reconstruct it, for about 18 months. Is that right? Figuring out what's next?

Yeah. It took me a while to exit and sign agreements and get out. They were kind of mean. And then I stepped into an office, and it was late. We went for a nice, long vacation and stuff like that. When I got back in September, so that was six months later, I went to my... I started going to work. Yeah, I had nothing to do, but I went from 9 to 5 and started calling people and thinking about what I'm going to do. It was in the Seagram Building, so I'd go for lunch downstairs every day.

At the Four Seasons.

At the Four Seasons. And I explored everything, thought about my own merchant bank. I could have retired just teaching, just investing, but I was 42.

You took a call about running Amazon, didn't you?

I went to visit Jeff Bezos, who was looking for a president at the time. He and I hit it off. We've been friends ever since. He's an exceptional human being, but it was like a bridge too far. Even though that movie had just come out, *When Harry Met Sally*, I was thinking, "My God, I'll never wear a suit again. I'm going to live in a houseboat. This would be really great."

What an alternate universe we'd be living in.

It would have been an alternate universe. But I'm still good friends with Jeff, so I got at least one good thing out of it.

And then I got serious, and I was offered jobs to run other big global investment banks. Hank Greenberg, who ran AIG, called me up and said, "You should come join us." I was thinking, "I'm going to go from Sandy Weill to you. I'd have to have my head examined to do something like that."

I didn't know the AIG story.

Yeah, well, that happened years later, too. And then I got a phone call from a headhunter about Bank One. And I was also... You guys, a lot of you probably know Ken Langone and Bernie Marcus and Arthur Blank, who ran Home Depot. I loved them. But at my first dinner with them, I went to see them in Atlanta. I said, "I have to make a confession. Until you guys called, I had never been in a Home Depot."

And we were actually wondering. David and I were debating.

We were talking about this. You're a lifelong New Yorker.

My friend made me go up there and get some equipment and plants and stuff like that. But I love their culture, their attitude. They wanted me to do it. Ken Langone says, "I still should have gotten you. I wasn't going to pay you enough." Of course, it had nothing to do with anything like that.

And I had Bank One, but Bank One was my habitat. I was used to financial companies, services, and banking. It wasn't quite global. It was a little global at the time. And it was a troubled bank. And I decided that life is what you make it. It was hard in my family. We had to move. I think for anyone who's going to move kids—I think they were 14, 12.

It's hard.

Some context on Bank One: For folks who are not familiar, it's not in New York. It's a large bank, but it's a troubled bank. It's based in Chicago.

When you say large, David, it's a $30 billion market cap bank. Citigroup, where you just had been before, was a $200 billion bank.

It was 21 billion at the time. Because you have the right numbers. But it did a split. And so if you look back, it was more like 20 billion or something like that. Yeah. And Citi was 200. But I didn't worry about that. It was like, in life, you make things what they are. I don't like complaining about over spilled milk. You just put on your pants, get going, and see what you can make out of it.

But you... it sounds like you had opportunities to stay in New York to run.

I did.

Bigger, more glamorous businesses.

This one, I was going to run the company. The other ones would have been some investment banks. I didn't really trust some of the people who were talking to me about that. And there's a whole bunch of other stuff that I explored. I took phone calls from some small companies, some big companies. There's a couple of subprime mortgage companies who called me, and I was like, "Absolutely not."

We'll get to that, we'll get to that.

That, we'll get to that. And so I just thought this was a chance. If the family's willing to move, and we got a nice... Took us a while. We had to live in a rental for a while, but got a nice brownstone, and we ended up loving Chicago. Chicago is a wonderful city in a lot of different ways. And, like I said, it is what you make it. And I put half my money in the stock at the time.

Yeah.

Yeah.

I tied my... I was going to be the captain of the ship. I was going to go down with the ship. I made it clear to everyone I was here permanently, and it will be what it is. And so I got to work literally the next day.

Did we do the math right, that, right before you joined Bank One, you bought $60 million of stock?

I did.

I mean, I've never heard of someone taking a CEO job and saying, "I'm going to invest half my net worth in this company now."

Yeah. And I thought it might be overvalued a little bit, because there was... people thought it might be sold or something like that, but I didn't care about that. If you work at a company and the new CEO comes in, he's from out of town, and you're going to have a lot of shareholders. And I knew a lot of the shareholders. I was going to know a lot of the shareholders. I wanted to know. I was in 100%, lock, stock, and barrel. There was no question I would never sell that stock. And I'm going to go down with the ship or go up with the ship. And they also knew I was making decisions that I thought were right for the long-term health of the company, not for a short-term type of thing.

So what did you find when you got there? Day one on the job, you start investigating. Is it better, worse, or the same than you thought?

You know, there had been an analyst called Mike Mayo who had done a report. I remember one of the great lines in the report: "Even Hercules couldn't fix it." It had been an amalgamation of Bank One, First Chicago, National Bank of Detroit. They'd never put the companies together. So they had multiple statement systems, processing systems, payment systems, and SAP systems. They had different brands, services coming down. We were losing accounts, they were closing branches. It was a mess.

But it was all of it: systems, people, ops. But again, I just... I met the management team. It's hard. I walked in and met six of the directors. There were 21 directors; 11 hated the other 10.

Yeah, wait, wait, wait. There were 21 board members? Twenty-one board?

Members from the merge, multiple acquisitions. They were tribal. They ended up hating each other. I knew that when I went in because I knew one person and I spoke to a lot of people and did research in the bank. But again, in life, you get handed these things, and it's not perfect. Even today, people want to be handed something perfect. It's not perfect.

So I met six of the directors. I walked in when I got offered the job. I shook all their hands. I told them, "I'm going to do the best I can. I'm going to tell you the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth: the good, the bad, the ugly. We're not going to bullshit. We're going to try to build a great company. I'm going to need your help." And then, they left. So now I'm on the executive floor. I don't even know where to go. So I kind of knocked on someone's door, the head of HR. I said, "I do need an office and I really need an assistant." And they were going to give me the chairman's office in the corner. I said, "No, no, I want to be right in the middle so I can see people and stick my head out."

Then I went to meet the management team. I went to this... They put them all in this conference room. Nice, white, plush carpets. I walked in with a cup of coffee, and they said, "Jamie, we don't drink coffee in here for obvious reasons." So I looked at them, I looked at the coffee. I looked at them, I said, "You do now?" Then I just started meeting with them all, and the systems were terrible. The company was losing money. I didn't know all the businesses really well. The credit card company had collapsed; that's probably the business I knew the least. But again, that didn't matter to me; I was going to try to fix it. It had some good assets and things like that. So I rolled up my sleeves and went to work.

And when we were chatting a couple weeks ago and preparing for this, we asked you in the context of JPMorgan: what are the critical things in your mind that have made JPMorgan what it is today? And the first thing you said was risk, and the culture around risk.

A fundamental understanding by management of risk.

Yeah.

When you got to Bank One, I think this is where you first started putting into practice the culture around risk. What was the risk culture at Bank One, and how did you change it?

Yeah, I've always been very risk-conscious. Risk-conscious does not mean getting rid of risk. It means properly pricing it and understanding the potential outcomes. So when I got there, I just started meeting people and going through it. I quickly realized that Bank One had more U.S. corporate credit risk than Citibank did. The way they accounted for it was unbelievably aggressive. So they had less capital, less reserves, less of this. They were calling these things profitable; they were basically losing money on loans.

In a lot of businesses, you've got to be very careful about the credit business. Once I found that out, I kind of panicked a little bit. I went through every single loan in the books, marked them all down, put up more reserves, told the board about it, and then wanted to earn more revenues per dollar of risk. I always stress-tested and showed the board that if we were to have a recession (and we were about to have one), how much money we'd lose in credit.

So I hired a woman called Linda Bamman, who said, "Okay, if you're going to let me do credit, are you going to let me sell loans?" They said yes. "Are you going to let me hedge loans?" "Yes." "Can I do 10 billion?" I said, "Yes." She said, "Okay, I'll join." And we probably reduced the balance sheet by $50 billion. Then we did have a recession, but we were kind of okay by then, with one big bad one, which was United, which went bankrupt, and we basically owned it for a small period of time.

There seems to be a fundamental Jamie Dimonism, which is "Don't blow up." I mean, a lot of other people have gotten decent at pricing risk, but everyone else seems to be willing to get closer to the line than you. Where did you develop this "don't blow up at all costs" mentality?

So, around risk, there's always this ecosystem. You've always heard it: "Everyone's doing it, everyone's okay, this is going to work. This time is different." And history teaches you a lot. And I always say, my dad was a stockbroker, so I bought my first stock when I was 14. In 1972, the stock market hit 1,000. It had hit 1,000 in 1968. I was already helping a little bit with stuff. By 1974, it was down 45%. All the limousines on Wall Street were gone; restaurants were being closed. Markets move violently. Then we had a kind of recovery. In 1980, you had a recession. Then in '82, you had another recession. It was lower than it had been in 1968, and it hit 800. Then in '87, the market was down 25% in one day.

In 1990, all these banks—JPMorgan, Citi, Chase, Chemical—were all taken to their knees by real estate losses. They were all worth about a billion dollars. I think Citi was $3 billion at the time, and the other ones were about a billion dollars. Then you had the '97 (also real estate-related) thing. You had the 2000 internet bubble, and then you had the Great Financial Crisis. And if you go through history, there are tons of these things. Andrew Ross Sorkin is in here, and I just read his book. He was nice enough to send me his book on 1929. And man, history does rhyme. Too much leverage, too much risk. Everyone thinks it's going to be great. No one thinks it can go down a lot. That stock market went down 20% one year, 30% the next year, and 20% the year after that. At one point, it was down 90%. Shit happens.

It seems like your philosophy is: "The worst thing will happen, so just plan for it."

The.

Don't say, "Oh, we're good, as long as this crazy, insane four-sigma event doesn't happen." You're like, "No, that will happen, and it happens often."

Yeah. So when I look at it, I always ask—like when I do stress-testing at risk for high yield... I remember getting to JPMorgan and going through the risk books; their stress test was that high yield would move 40%. The credit spread at that time was at 400 (or whatever it was), meaning 560. Okay. And I said, "No, our stress test is going to be worst ever." Worst ever was 17%. And they said, "That'll never happen again. The market's more sophisticated." Well, in '08, it hit 20%, and you couldn't have sold a bond. There was no market. So those things do happen. The point isn't that you're trying to guess; the point is you can handle them. So you continue to build your business.

So I always look at what I call the "fat tails" and manage that. We can handle all the fat tails—not just the stress test the Fed gives us, but all the fat tails. Market's down 50%, interest rates up to 8%, credit spreads back to worst ever. Of course, your results will be worse, but you're there. And the thing about financial services: leverage kills you. Aggressive accounting can kill you, which a lot of companies do. And, you know, the goal should be... Also, confidence: if you lose money as a financial company... I always knew this, too. The headlines are... people read that, and they're relying on putting their money with you. They look at that difference, they lose trust. They lose trust. And that was because you've seen runs on banks—and you saw some recently—because people run to take their money out.

There's a thing that you just said, which is that you might do worse, but you're there. There's this trade-off that you make where you're less profitable in the short term, but at least you stick around. If you look back at the companies that you've run, including JPMorgan Chase... Is that true in the good years that you've actually been less profitable than those who are "risk-on"?

Yeah, a little bit. He's saying that if you look at the history of banks up until 2007, a lot of banks were earning 30% equity. Most of them went bankrupt. We never did that much. But in '08 and '09, we were fine, and they weren't. But you want to build a really strong company with real margins, real clients, and conservative accounting where you're not relying on leverage. It's very easy to use leverage to jack up returns in any business. But in banking, it can be particularly dangerous.

So it seems like a core part, if not the entirety, of this distilled into your operating strategy is the "fortress balance sheet." When did you first hear about the "fortress balance sheet"?

I've been talking about it; I go way back to Primerica. I used to talk about that: you've got to be able to survive. Early '90s, probably the 1990s. And like I said, my father and I went through those market things. I remember how hard it was on people on Wall Street. But the "fortress balance sheet" is... you run a company serving clients well. You have good margins, good liquidity, good capital. I'm as conservative an accountant as you can find. I don't upfront profits, but I can spread them over time in accounting. Of course, accountants hate it when I say this. You can drive a truck through accounting rules, and accounting itself—certain things are considered expenses, but they're good. They're an investment for the future, but they're called an expense.

And then revenues... if I make bad loans, they are bad revenues; they will kill you. But for a while, they look pretty good. So it's all those things: margins, clients. In the banking business, the character of the clients you have will reflect in your bank. So the first thing is: who are you doing business with? And how are you doing business? And also making sure your compensation plans aren't paying people for stuff that's stupid or unethical. And you always have to review these things to make sure you have them right, because they change all the time.

All right, David, catch us up to the merger.

So you ran Bank One for four years from Chicago, and then in 2004, you merged with JPMorgan Chase in what was termed at the time a "merger of equals." I think JPMorgan Chase referred to it as that; Bank One shareholders got 42% of the combined company. I mean, I think people don't realize how much of JPMorgan Chase is Bank One today.

That's why it's a little irritating when they say you've been running it, since I was running JPMorgan, I was running 40% of the company for the whole time. When I got to Bank One—and I'm not working around the clock—I already knew that a logical, strategic merger might be JPMorgan. I know all these companies. And that's the other thing about a "fortress balance sheet": you also have real strategies that survive the test of time. You're not flipping and flopping. And then I'm sitting there, and of course the tape comes: "JPMorgan Chase to merge." So we're worth like $25 billion. They're now worth like $80 billion or $90 billion, or whatever the number was. I'm like, "Well, there goes that dream." But four years later, our stock had doubled or something like that. It had actually come into the target range. And I had been meeting with Bill Harris, who was the chairman of JPMorgan at the time. We were talking about it; we both knew it made business sense. They were looking for a CEO. So we were... We had been talking probably for a year and a half before that.

They're looking for a CEO. Did they give Bank One shareholders 42% because they were looking for a CEO?

So we got the premium; they got the name and location. And I effectively had control from day one because, inside the merger agreement (and this is almost unheard of when we get the premium), it stated that for me not to become CEO... eighteen months later, 75% of the board would have to vote me out.

But the default was that you were going to become CEO.

To become CEO. And the board was eight Bank One people and eight JPMorgan people. But that was the agreement. They got sued for paying too much to buy me; I got sued for not taking enough. You get sued; you can't win in these situations.

I think every shareholder is probably happy now.

But it worked out.

Yeah. When you were going through that process, and even maybe the couple years before you and Bill were talking, you were starting to think about JPMorgan as a partner. I'm curious: did the brand, did the name JPMorgan, factor into your thinking at all? Did you view that as an asset?

I mean, the JPMorgan brand is a Tiffany name. I didn't value it in the deal. And when I looked at... I had told my board, "I think the first thing is to run your company well." And people thought I was going to start doing deals immediately. I was like, "No, we suck. We don't—we haven't earned the right to run someone else's company yet." When we're running a good company, we can merge with somebody. But the first thing I looked at was business logic, and that was for every business. We had a consumer business, they had a consumer business. We had a credit card business; they were both terrible. They had a credit card business, they had a big investment bank. We had a big U.S. Corporate Bank that needed some of those investment banking services. We both had a wealth management business. I knew we could save a lot of cost savings. So the business logic was pretty impeccable. Then there's the ability to execute: Can you actually get it done? Because you've all seen a lot of deals where they fall apart. They don't have management, they don't consolidate the systems, and they have infighting. It kind of happened at Citi, so you don't effectuate the merger. And then there's the price. So I knew we had a Tiffany brand, but I didn't value it because if everything else didn't work out, I don't think it would have mattered that much.

Interesting.

Okay, so I'm going to fast forward a couple years. It's 2006; you're officially chairman and CEO of the combined JPMorgan Chase.

And 2006 on Wall Street is like, "Go, go, go, go, go, baby!" It's like the 1980s all over again.

I think you had the same incentives as everyone else, but you behaved very differently. Am I missing something? Did you have the same incentives, or...?

Did you pull JPMorgan back hard on the risk side in 2006?

I did. So there were cracks out there in 2006; you may remember the "quants." There started to be a quant problem. Late in 2006, we definitely saw subprime getting bad. And I pulled back on subprime. I wish I had done more, because if you look at what I did, you'd say, "Okay, you saved half the money, but you would have saved more."

You still had some losses.

Yeah, but we also had, I'm going to say, less. Maybe a third of the leverage of the big investment banks and a lot more liquidity. So in 2006, I started to stockpile liquidity. And looking at the situation, I was quite worried. The leverage... you may not remember this, but the leverage, because of accounting rules and Basel III (and Basel I), for investment banks (particularly the big investment banks) went from 12 times leverage to 35 times leverage. And it was "go, go," with CMOs, bridge loans, the whole thing. Like in '07, the bridge book on Wall Street was $450 billion. Today it's $40 billion. JPMorgan can handle the whole $40 billion today, though we're not doing all $40 billion today. And they were much more leveraged deals; a lot of them fell apart, collapsed. And then, of course, that was before you had the collapse in the mortgage markets, which really took down a lot of these banks.

But you did have the same incentives and you had the same access to information that a lot of these other folks did, but you didn't blow up. What explains this, because usually behavior follows incentives?

Yeah. Well, first of all, if you work for me, I would tell you I don't care what the incentive is. Don't do the wrong thing, and don't do the wrong thing to the client. If you treat yourself—if you're the client—how would you want to be treated? And I had gotten rid of—I mentioned that one risk thing... There were multiple risk things like that. They were being paid to take the risk. All of these investment banks were doing side deals, private deals, three-year deals, five-year deals. I got rid of almost all of them.

This is for comp.

Almost all of them, senior bankers. So today at JPMorgan Chase, there are no—we do do things, and I know some of my partners are in the room here—but we all know about it. There are no winks, no nods, no side deals. There's almost no one paid on a particular thing. Because if you're paid on a particular thing, you can do the wrong thing. And meanwhile, you're not helping the company manage its risk or something like that. So we changed the incentive programs, and I'm quite conscious about incentive programs that they don't create misbehavior. But it's also very important. If you're in a company and you say the incentive program is doing that, you should tell the company: "This incentive plan is not incenting the right behavior versus the customer." And a lot of it was leverage. So if you look at the leverage in some of these securitization books and mortgage books, if you have 30 times leverage and you're getting 20% of the profits, you'll go to 40 times leverage. It's just going to... it's literally 25% to your bonus. So I got rid of the profit pool (20%) and the leverage.

So.

Yeah, and I lost some people in the meantime, too.

It's funny.

Yeah.

JPMorgan, as part of the system, had the same incentives, but you changed the incentives for pretty much every team within the company. Okay, all right, we've got to go to 2008.

March 13, 2008.

Thursday, March 13, 2008. It's Thursday night. You got a call from Bear Stearns' CEO. The stock closed that day at $57 a share. It was like $150 a couple months before. Three days later... God, I remember it like yesterday. I was working on Park Avenue on Wall Street. I remember that night: $2 a share. You're buying Bear Stearns. Tell us the story.

So I was at Avra on 47th Street—my parents' favorite restaurant. My whole family was there. It happened to be my birthday. I don't normally get emergency calls. Yeah. And Alan Schwartz, who was the CEO, we'd seen their stock go down. I knew they had some real problems because we saw the hedge funds and some of the things that were taking place there. And he said, "Jamie, I need $30 billion tonight before Asia opens." I said, "I don't know how to get $30 billion for you." "And have you called Paulson? Have you called Tim Geithner?"

So we all called. I called up the management team. I went back in; I probably had a bite and said goodbye, then went back to the office. Probably had 100 people come in that day—that night. They all got dressed, they went back to work. It was an emergency. We rang all the bells for an emergency. Bear Stearns went bankrupt. I spoke to the Fed about, "Let's just get them to the weekend." We had one day, and we needed Saturday and Sunday. We concocted this loan so we couldn't lend the $30 billion, and the Fed technically couldn't lend the $30 billion, but the Fed could lend to us technically, and I could technically use the collateral of Bear Stearns.

So we got the literally one-day loan, and then the next day, we had thousands of people come in for due diligence. And we went through every loan, every asset, every balance sheet, all the derivatives, all the lawsuits, and all the HR policies—like real due diligence—over a two- or three-day period, and bought the company that night for $2 a share. Hank Paulson was saying, "Why are you paying anything for it?" I said, "Well, I do have to get shareholder votes." And which became right, because you need...

Bear Stearns shareholders to approve the deal.

It was a public deal. And the worst part of it is, I was going to get the lawsuit from the Bear holders. I knew that you didn't pay enough. But we couldn't let it go bankrupt.

It wasn't like an industrial company you can buy in bankruptcy. It would have been gone, and the crisis would have just unfolded.

So we paid a billion dollars for a company that had been worth $20 billion recently. The building we're in now was worth a billion dollars on the balance sheet for zero. And we got some very good people and we got some good businesses. But it was an extremely painful process.

I've seen estimates that in the fullness of time, after really dealing with unwinding all the stuff there, it cost you 15 to 20 billion dollars.

The $12 billion we wrote off didn't cost us. We didn't really pay for it.

And then the government sued us on the mortgages, which I was quite offended by, and I really was. I thought it was his problem.

And then, this is the government. When, whatever government you did a deal with, that's not the government down the road that decides, "I don't care, we're going to come after you anyway."

So, while we kind of saved the system a lot, we bailed a lot of people out. They made us pay $5 billion on the bad mortgages that Bear Stearns had done. And that's what made me make the statement I wouldn't do it again. I wouldn't put it this way. I don't know how to say this: I wouldn't really trust the government again. Okay.

I've got to ask a follow-up question to that. Is that a structural thing, just the way that we're set up with a new administration every four years?

Yeah. They don't feel obligated to what the prior administration did. And even some contracts were violated in this thing, which I won't go through, literally, contract. I mean, it would have been tortious interference had it been company to company. But they basically, since you operate under their laws, they can basically take you down.

So, I went to see Eric Holder trying to settle this mortgage stuff, which we settled. I put my lead director... He expected me to come and be pounding my chest. And I went in and said, "Eric, I am here to surrender. I cannot fight and I cannot win against the federal government. You know that a criminal indictment can sink my company. I will not do that to my company or my country. I'm here to surrender."

Before I surrender, I want you to know the circumstances by which we bought WaMu and Bear Stearns, because 80% of what they're asking for related to Bear Stearns and WaMu, not JPMorgan Chase.

And I went through the whole thing. He said, "Thank you, I'll take it into consideration." But they never gave me the accounting, so I don't know what they did. And so it is what it is. It was quite painful, but I've got to move on.

We'll move on from this. We won't keep you.

Well, we'll move on from the specifics. David's like, I do have one more thing. Whether you would have done it again, or wouldn't have, it's very clear. It was not a great deal on paper for JPMorgan. But as we look at it now, the reputational value that JP... the reputation of JPMorgan now is unlike any other in the industry.

Part of why you're worth $800 billion is that reputation. A lot of what created that reputation...

Was that weekend.

Yeah. Yes. And I know I say I wouldn't trust the government. If the government called me up... If they called me again and said, "We need your help to save our country," of course I'm going to. I'm a patriot that way.

I would just try to come up with some ways to avoid the punishment by the next president. I would come up with something.

You know what you need? Like a version of the merger agreement with JPMorgan Chase where 75% of Congress needs to vote not to sue you. The default is you're not going to get sued. All right, all right, all right.

So Bear Stearns happens. Six months later, you get another phone call. WaMu is going under. You do buy WaMu. Contrary to everything we're talking about with Bear, WaMu is actually a great acquisition. Right?

Yeah. So this is a lesson about acquisitions. It's very hard. Remember, we bought WaMu a week after Lehman went bankrupt. And most boards wouldn't have touched that.

At all, because the whole system feels...

Like the whole system was in trouble. But WaMu put us in California, parts of Nevada, Arizona — no, not Arizona — Georgia, Florida, which we weren't in. So think of these really healthy states.

And they had 2,300 branches. They had huge mortgage problems. But we had looked at it over and over and over. So we knew their mortgage books cold, and we wrote off losses. We bought it for...

And this was all before...

We bought it for $30 billion, discounted to tangible book value because they had debt, and we left the debt behind.

And that $30 billion was approximately what the mortgage loss was going to be. So we bought the company. Think of it. We bought a company clean. We wrote off all that stuff. The books were clean.

And then we did something unheard of, too. The next day or two days later, I went in the market, raised another $11 billion of equity, which I didn't really need. But again, this is my conservatism. I was like, "You know what? This can get even worse."

And I don't want to be short capital or liquidity. So we raised that to make sure our balance sheet was just as strong after WaMu than it was before WaMu.

And you already had the reputation to pull this off, right? I'm imagining in the worst month of the financial crisis, who can go out and raise $11 billion of equity?

Yeah.

People trust you.

Well, yeah, we knew a lot of shareholders, and you earned your trust over time with shareholders.

And we explained, we gave them a quick little presentation. Yeah. A lot of them stepped up and said, "This is great." They also know we can execute it because behind the Bear Stearns acquisition, people forget the work. The next day, you had 50,000 people consolidating 5,000 applications, branches, compensation programs, settlement programs, payment systems. It's a lot of work.

But we obviously have the capability to do that, and we have the capability to do WaMu. I think we finished the WaMu consolidations in nine months — all of them. So that within nine months, they were all in the same systems, which allows you to start doing a better job in customer service and things like that.

So this fortress balance sheet strategy, raising this equity capital, and having additional margin of safety and conservative accounting — in retrospect, it seems like the obvious right strategy for running a large financial institution. Why wasn't everyone else copying it? Have people changed, and does everyone else run their banks like this now?

I think people are more conservative today. I think regulators are more conservative today. But again, I go back to people get involved in aggressive accounting; they don't look at stressing their own bank in a real way.

You saw people take too much interest rate risk, too much credit exposure, too much optionality risk, or sometimes it's new products. So if you look at the financial services, very often it's the new products that blow up. It takes a while. They haven't been through a cycle.

And you had that with equities way back in 1929. You had it with options, you had it with equity derivatives, you had it with mortgages, you had with Ginnie Maes. Even Ginnie Maes at one point blew up even though they're government guaranteed.

Arguably you had it with quant and with LTCM.

It happened with leveraged lending. And then people become more rational in how they run these balance sheets now. They think through the...

So I have to ask you, is this private credit today?

I don't really think so. I don't think it's $2 trillion. It's grown rapidly. That's an issue. But the other thing about markets is there are some very good actors in it who know what they're doing. Customers like the product. So I always say, the customers like it, but there are also people who don't know what they're doing, and it's grown rapidly. So there may be something in there that would become a problem one day, but I don't think it's systemic.

So that $2 trillion... the mortgage market, when the market blew up, was, I'm going to say, nine trillion, and a trillion dollars was lost. This is, and it was...

A trillion dollars was also in a...

Highly leveraged.

Back then.

Yeah, a lot of these private credits are not leveraged. That doesn't mean there won't be problems. But it's slightly different. But if you look at the whole system, there are other things out there that are leveraged that can cause problems. Of course, people take secret leverage in ways that don't necessarily... I see it.

What are some of these in your mind that are potentially problematic today?

Well, look, when you look at asset prices, they're rather high. I'm not saying that's bad. But if today P/Es were 15 as opposed to 23, I'd say that's a lot less risk, a lot less to fall. And you have some upside. I would say at 23, there's not a lot of upside, and there's a long way to fall. And that's true with credit spreads.

So, we stress test everything. We do like 100 stress tests a week to make sure we can handle a wide variety of things.

And then the other thing, and the biggest risk to me, is cyber. I mean, I think this cyber stuff is, we're very good at it. We work with all the government agencies. They would say the chamber, we spend $800 million a year or something on it. We educate people on it. We just do.

But it is... you're talking about grids and communications companies and water and even part of the military establishment. The protections are not what you need if we ever get any kind of war where cyber is involved. And China is very good at it, and so is Russia, but Russia is mostly criminal, which is slightly different.

All right, I'm going to pull us back to the story. We're going to fast forward to 2023.

We're not really equipped to talk about Russia. It's not what we do on Acquired.

But, Silicon Valley Bank...

Yeah.

And First Republic both fail. You're there again. Did you see it coming? What lessons did you learn from how 2008 went that you could apply in 2023? Obviously, you bought First Republic.

Silicon Valley Bank did some very good stuff, but they both had something unique that we didn't know at the time. I'm going to call them concentrated deposits. Not uninsured, because people were misstating that. Concentrated.

And so a lot of venture capital... What happened to Silicon Valley Bank and First Republic is some of these large venture capital companies — call them, there are hundreds of them, maybe a thousand — told their constituent clients that they invested in, who all banked in Silicon Valley and First Republic, "The banks aren't safe. Get out." And they all removed their deposits.

At Silicon Valley Bank, I think they had 200 billion in deposits; 100 billion in one day. And that caused the problem. But they also had other problems. They didn't have proper liquidity. They didn't have their collateral posted at the Fed, and they had taken too much interest rate exposure.

And the interest rate exposure was hidden by accounting. It was called "held to maturity," where you don't have to mark even Treasuries to market. And I always hated held to maturity, but it gives you better regulatory returns and stuff like that.

But when that "held to maturity" [asset was re-evaluated], if you said, "What's the tangible book value of one of these banks?" And you said it was 100, all of a sudden it was 50. If you just marked that one thing to market, now you're into judgment land.

At what point, if you saw a bank where just that one mark had the tangible book value drop to 40 or 30 cents to the dollar, would you panic? I would have said, "That's too much risk."

And the regulators helped us because they said rates were going to stay low forever. So these banks bought a lot of 3% mortgages. And when 3% mortgages, when rates went up to 5%, were worth 60 cents on the dollar or 50 cents, that was it.

And so both of those had [issues]. They took too much interest rate exposure, known to management and the regulators, and it was fixable.

So we knew a little bit about Silicon Valley Bank. We were trying to compete in that area. So we learned a lot afterwards about how to do a better job for that ecosystem of venture capital. We have a whole campus in Palo Alto now. We've hired 500 innovation bankers. We cover venture capital companies. We're not as good as they are yet. We're going to get there because we're organized slightly differently.

And we knew First Republic. We were watching it. I called Janet Yellen. I said, "That company's in trouble." And one or two others, if you want, we'll take a look. We could probably buy it and eliminate the problem. They waited a little bit too long. A melting ice cube.

But you can imagine, the day we bought it, you never heard about it again. We hedged all their exposures in a couple of days. And we merged everything, we wrote everything down.

But we did get some good stuff. We actually got some good people. The normal thing in an acquisition is, "They're terrible, get rid of them" or "They failed." But we also looked at what they did, how they dealt with clients. Let me be clear here. They did a great job with high-net-worth clients. Single point of contact, concierge services.

So now if you go down Madison Avenue, you see things called JPMorgan Financial...

"Center." That's your first JPMorgan branded consumer effort, right?

Yes, because it's based on that. When you walk in there, we know your small business, we know your mortgage, we know your consumer banking. We can get you travel, we can do a whole bunch of different stuff.

So very high-level services. I think we have 20 of them now, but I love it. And if it works, in 20 years we'll have 300. And so these things are opportunities, and I hope it works. You don't always know they're going to work for a fact, but so far, so good.

All right, so we're effectively caught up to today. And if we're trying to... Now we've got the whole story, we've got a lot of context. Obviously, it didn't go into every detail. But if we're now trying to answer civilizer. Yes. If we're now trying to answer the question: how did you separate from the pack? Why did you become a completely different animal than your whole competitive set? What are the things in your mind that led to this success?

What we do is the same thing that a community bank does — other than investment banking, global investment banking.

Okay. So if you walk into a small community bank, they know your business account, they know your consumer account. They usually have a trust company; they used to call it trust. They manage your private affairs, they set up a trust for you, and they do stuff like that. And their CRM is up here. They don't need a Salesforce CRM because they know everyone in town.

And they didn't do big-time global investment banking. But the strategy: those businesses fit together, they feed each other, and so does investment banking. A lot of our middle market clients use investment banking products. A lot of our consumer clients use some FX. So all of our businesses feed each other. There's nothing extraneous. We got rid of everything that didn't fit a strategy.

And then you start building client businesses and client services: fortress balance sheet, fortress accounting, all those various things. And I've always talked about...

So it's holding a portfolio of things that actually feed each other, that actually fit.

Whereas Citi had consumer finance that didn't fit, life insurance that didn't fit, and property that didn't fit. They eventually got rid of them all. Sandy just wanted to do more of them. He bought American General, which did truck leasing, for God's sake.

And once you get involved in these things, it's hard for people to understand the risk in each one of these businesses. But all of ours fit. I don't like hobbies, I don't like things.

And we've made plenty of mistakes because you have to try and test things, and then you're always investing for the future. That investment is always people, branches, and technology.

And that's true whether it's investment banking people or consumer bank people, or opening consumer branches, or, I think Doug Pennos here and Troy Rohrbach who runs the global investment bank... But they've opened commercial banking branches all over Europe. And I think you're telling me — I mean, it's going great — and it's feeding all other parts of the company.

So just sticking to your knitting, constantly investing, not overreacting to the market. Markets are like accordions. And then sometimes it's a... If you're strong when others aren't, you have a chance to buy things you want to buy.

And then always look at the world from the point of view of the consumer. What do you want? How do you want it? How do you want to get it? Can we provide it to you in a way that makes sense for us, too? Not going for the last dollar and nothing like that, and building teams of people.

Our people are curious and smart. They have heart, they have soul. They give a damn about the guards in the company and the receptionists. It's not just about the big-time bankers and people pounding their chest. We don't try to... try not to put up with that. And we have big-time bankers; they are exceptional. But the company serves the clients. And I think the clients know that.

When you really dig in to start analyzing JPMorgan's financials, you see this one thing that jumps right out at you, which is the efficiency ratio. For every dollar that you make compared to your competitors, you get to keep $0.15 more of that dollar as profit. It's not hard to see how that compounds and how that allows reinvestment. And why is your efficiency ratio so much better than competitors?

It is literally continuously investing and gaining business at the margin, and not stop-starting. And the thing about margins, too, is that we have that margin while investing a lot.

It's much easier to have that margin, and we can cut billions of dollars of marketing out tomorrow. We can stop opening branches and save a billion dollars next year. We could do a lot of things. Your margins will go up, your growth will go down; your long-term margins will probably get worse.

So we look right through the cycle, and we look at the actual economics that we do, not the accounting of what we do.

And we've built it over time. We have great people and great products, and there's some secret sauce I'm not going to tell you about. We do Investor Day, and we tell everyone everything.

And I'm sitting there watching my... I never do presentations. I'm watching them do the presentations. I'm saying, "Oh God, we're just giving away too many secrets here!"

But, so there are secrets as to...

Why... I saw Howard Schultz here before, and I'm not supposed to say that.

Probably it's okay, but...

No, but we're glad you invited your friends. Look what he built over the years: the consistency, the curiosity, the heart, the branch-by-branch products. It's just always doing that, knowing you're going to make mistakes, but building the culture that just plows through that.

And you all know I do use sports. Sports is a great analogy. If you have a sports team with a bunch of real jerks on it, are they going to be a great team? Almost never. If the team members aren't giving it their best every day during practice? You heard Tom Brady: every day at practice, he worked hard. If people are not giving their best, you're *not* going to have a great team. And it's not that different in business. The difference is, in business, you can BS about it all the time, you can make up stories, but in sports, you see it on the playing field. Do they play as a team? Do they play together? They don't even have to be friends. They have to practice, know their teams. And so I do think companies have that. It's like a sauce that works. And you've seen it in lots of different companies, not just JPMorgan Chase.

All right, we've got one last question for you. If you look back to 2008—which was a long time ago now—or to the 2001 to 2008 era, all of the other leaders that were involved in that era have long since retired. I think many folks within JPMorgan Chase have long since retired since then. It seems like you're working as hard as ever and in it as much as ever. Why are you still here? What keeps you going?

Yeah. So I want to thank my wife, who's here too, who suffered through all this with me all these years and probably couldn't have done it without her. I don't know. But I do believe—my grandparents, all Greek immigrants.

There we go.

My grandparents were all Greek immigrants who didn't finish high school. But there's a Greek ethic, and you don't even realize you learn it from your parents, from the ground up. And Judy's parents, my wife's parents, were the same, which is: have a purpose. It could be art, it could be science, it could be military, it could be business, it could be just being a great parent, a great teacher. But have a purpose and then do the best you can; give it your all. Don't be one of those people who's complaining all the time. You give it your best and then treat everyone properly, everyone, including if there's a bully beating up on someone, you had to stand up for that someone. You were not allowed to let a bully do it. So, how you treat people, what you do.

And so in my hierarchy of life, the most important thing is my family still is. The second thing is my country, because I think this country is the indispensable nation that brought freedom of speech, freedom of religion, freedom of enterprise, which we have to teach everywhere we go about how important it is. I don't think people fully understand it sometimes. And then my purpose, because my family doesn't want me home every day. And this is my contribution: through this company, I can help cities, states, schools, companies, employees. And I get the biggest kick out of that. And so that's what I do. And as long as I have the energy, I'm going to do it.

I can't imagine. I don't play golf. One of my daughters said, "Dad, you need some hobbies." And I said, "I do! Hanging out with family, travel, barbecuing, wine." We now like whiskeys. And I love history. I think history is the greatest teacher of all time. Hiking. I can't play tennis anymore because of my back. But those are my hobbies. I don't buy fancy cars and stuff like that. But this gives me purpose in life beyond family and beyond country. Plus, I think this helps the country. I get to do a lot of things for our country that I just think are quite meaningful from this job. So when I'm done with this, I don't know, I'll teach and write. I may write a book like Andrew Ross Sorkin did. I'll do something, but I've got to do something. I'm not going to twiddle my thumbs and smell the flowers.

There are a lot of people who have floated your name for political or policy roles over the years. There is only one job that could possibly impact the country on a bigger scale than you're currently doing. Do you agree?

Yeah.

Well, that's probably a great place to be. Jamie, thank you so much for joining us.

David, Ben, these guys are great, by the way. So thank you.

Jamie Dimon, everyone.

Thank you. Appreciate it. Thank you. Well done. Thank you so much.

Thank you.

Jamie.

Who got the truth?

Is it you? Is it you?

Is it you?

Who got the truth now? Is it you? Is it you?

Is it you? Only ServiceNow connects every corner of your business, putting AI to work for people.

Every corner.

Every corner. Nick. So, Kate in HR can focus on people, not processing. Patti in IT is using AI agents to deal with the small stuff so she can work on the big stuff. AI helps Jim solve customer problems before they become problems.

Oh, so we all work better together.

My work here is done.

Excuse me, which way back?

I started this brand because I started being told no—no to my dreams.

So I didn't have any design experience, I didn't have any business experience, but I really had a sort of belief.

Running a business is really challenging, but I love it.

This is so wild that I actually.

From a dream, started a business.

We're Cheekbone Beauty.

This is Super Ceramics.

We're Finished That.

We're Eastside Golf, and we're powered by Shopify.

Ladies and gentlemen, welcome back. I'm Andrew Ross Sorkin, and this is a late-night edition of DealBook meets Squawk Box meets Acquired. Please welcome back to the stage Ben and David.

Gentlemen.

Andrew. Hello.

Hello, hello.

It's so great that you're here. We're glad to have you here.

But why are you here? We've got this whole... I'm at the desk here.

I'm used to being behind the desk.

But we've got this late-night talk show with iconic New York company CEOs. We're going to be at the desk.

Yeah. I had heard that you might be doing something with The New York Times. And I grew up there, and so I just wanted to help you with notes, questions, research, whatever you were working on. Yeah, that's why I sat down.

No, no, I think we got it.

We did a whole three-hour episode a few years ago about The New York Times.

You don't need me for that.

I really appreciate you coming though. It means a lot.

Okay, if you know so much, can we just do a little quiz?

Yeah, let's do a little quiz.

Little New York quiz. We'll have everybody participate. Here's a big question for you. What year was The New York Times founded?

1851.

Bingo. Bingo, bingo.

That's top of mind.

Okay, that's one. Question two: Who once defended the New York Times building from the rooftop with a gun?

Yeah. Adolph Ochs.

Nope, nope, nope, no, nope. That was the original co-founder of the paper, Henry Raymond. But Ochs gets you style points. He bought the paper, by the way, from Raymond. Okay, this one. I wonder if this whole room is going to know this one: What iconic New York location is named after The New York Times?

Oh, Times Square.

Of course.

We have a billboard there.

And then, final question: Who is the most iconic CEO in The New York Times Company's modern history? And that person might be backstage as we speak.

We know this one.

Yes, we do! New York City, please welcome the CEO of The New York Times Company, Meredith Kopit Levien.

You've got to go over there.

It's great to see you.

That is great to see you.

That was fun.

A huge thank you to Andrew Ross Sorkin, everybody.

Good enough for Andrew Ross Sorkin.

I'll go anywhere Andrew Ross Sorkin goes.

And he is out late for taping at 6 AM on CNBC.

So, he's got to go get some sleep.

I think he is. I think he is.

Well, Meredith, it is great to have you here today. If there is one Acquired episode in the canon that is quintessentially, iconically New York, it's The New York Times Company, of course. And you guys, you're killing it.

As we talked about in our episode, in 2008, the company was on the brink of death. You had sold your headquarters building. And here, in the few short years since then, you are the largest digital subscription newspaper in the entire world. You are the only standalone global newspaper company left. Market cap of almost $10 billion, an all-time high. Publicly traded, things are going great.

Is that a question? No.

So, tonight... I mean, keep going, keep going.

Yeah, you just sit there, we'll just talk about you.

So tonight, it's been four years since our 2021 episode. We want to ask you about a bunch of things that have happened since then, sort of as an update for the Acquired audience and the Acquired canon. So first, how is the subscription business going, and what has stayed the same and what's changed since that big 2014 Innovation Report that changed everything?

Yeah, well, thanks for having me. I'm so delighted to be here with you guys. It's going well. It's going well. I think, where you left off, we had about 5 million subscribers in 2021. We are closing in now on 12 million. And the company is growing as you described. It's growing revenue, it's growing profit. I think more importantly, it's growing in its journalistic impact, it's growing in its cultural impact. And we really look out and see growth possibility in all directions.

Every week now, 50 to 100 million people are coming to The Times website and apps. Some 20 million or so people listen to our podcasts and read our newsletters. We've got about 150 million people who've registered with us, and that number is still growing. Millions of people use it every day. So that all feels like real growth possibility.

You ask about 2014. I'd say that's the year where we set a course for a long-term strategy about being essential in people's lives. Back then, print was still the lion's share; it was still the dominant engine of the business, and we were still doing great at the journalism. But I will say, we were getting our clocks cleaned by digitally native, upstart journalism companies at building a big audience for that journalism.

So, you asked me what's different now? I would say, one, print is... well, the newspaper is well inside of 30% of the business. We've got a huge engaged audience, as I just described.

Wait, the physical newspaper is still almost 30% of the business?

It's well inside. It's probably 20, 25%, but yeah, and by the way, it's going to be around a long time. People love it. The thing that I think we're going to talk about is that we've got a much wider product set now in every way: more coverage, more topics, more formats. We show up in people's lives in new and different ways.

And I think maybe the last thing I'll say is, culturally, we sort of found our way to go from playing defense to playing offense. We were defined back in 2014 by this big question: could we transform out of being a newspaper company? And I think now we're defined by our ambition for what all that The New York Times and journalism broadly can be and do in people's lives.

So what is the strategy then? You've expanded well beyond news: there are games, sports, Wirecutter, cooking, recipes. That means it's subscriptions to things beyond news.

It feels like in a lot of ways you guys have actually recreated what the newspaper was back in the day. It wasn't just news when you got a stack of newsprint every day or every Sunday delivered. It was lots of things: it was comics, it was shopping, it was classifieds.

I would sort of describe it as you are the largest first-party content company by subscriber count in the world. I mean, what other... It's more than a newspaper now. Am I thinking about that right?

Yeah. The easiest way to think about it is we are aiming to be the essential subscription for curious people everywhere who want to understand and engage with the world. And there are three ways we're going about that.

One, we want to be the world's best news destination. Hard stop. Two, through building and buying, we have these market-leading lifestyle products, and we want those products to help people make the most of their lives and passions. And we have put all that together in a connected product experience or bundle so that The New York Times is valuable in your life, whatever is going on.

So, build or buy. I mean, it sounds really good to have all this other stuff. Often these expansions fail at businesses; acquisitions fail. Oh, we're going to launch a cooking section, or a local section, that just fails comparison shopping. Why do you have, what, five, six, seven expansions now that are working?

What's the difference? Yeah, well, they've been a combination of building and buying. But I would say, in my time at The Times, there are three companies that we've bought — three things we've acquired — that have gone really well because they hang from that deliberate strategy I just described.

The Wirecutter, which is like a modern-day Consumer Reports for product reviews. The Athletic, which has, to our knowledge, the world's largest sports newsroom, at 550 journalists and counting. And then a little thing you might have heard of called Wordle, which we actually acquired the same week, because The Athletic was very, very exciting.

550 million? Single-digit million?

Well, we might have to do our...

Greatest Acquisition of All Time episode between the two.

But let me say the thing that sort of unifies all of them: these are experiences that sit in giant spaces. So there's a big market for sports, for games, for shopping advice, and for recipes. So that's one.

Two, I would say there are things where we felt like The Times could do something rare and really valuable. I talk about the size of that Athletic newsroom, and by the way, the Athletic audience is the fastest-growing audience on The Times. Because if you're a sports fan, where are you getting your really good, hardcore, in-the-locker-room sports journalism from?

And then they're also in spaces where people are doing something all the time. You're shopping, people. People shop all the time. Wirecutter drove something like a billion dollars of commerce last year. And the real magic of all of this is that the whole is kind of more than the sum of the parts. Each part of the portfolio and our news coverage feed each other. So, you know, it's just as likely for someone to come in to play a game and then read a story about the war in Ukraine as it is the other way around.

We were talking a few weeks ago about the importance of first-party owned and operated, you know, consuming The New York Times Company content on New York Times Company-owned sites. We feel the same way.

Please do that. Yeah.

In the age of AI, it's interesting, right, that you are a human-curated company. Everything that The New York Times does is human-curated.

Absolutely.

But a lot of the people in this room, they turn to AI to do a lot of the things that you just described. And yet, business is going great. How do you think about that?

Yeah. Well, let me say a few things about The Times and about AI. The first one is that we firmly believe that journalism, particularly journalism about important things going on in the world, is first and foremost a human endeavor. It is by humans; it is for humans.

You're not going to send—you might send a drone—but what they are going to find on the front line of a war versus a human being talking to people who've just been impacted... I think those are just like two different things. So that's one.

Two, we feel really optimistic that AI has the potential to be a force multiplier to everything we do. And what does that look like? It looks like making our journalism much more accessible to people. I'm a runner, and I now take in a lot of The New York Times text articles listening to an automated voice read them to me most mornings. And we're just at the beginning of that.

We have journalists who are using AI in some instances to comb through huge troves of public documents to get to a story in a better way. And I could go on and on, but the idea is AI sort of appended to 3,000 human beings doing journalism, making games, recipes, and so forth. It's the combination of those things.

And the last thing I'll say is I'm very optimistic about AI, assuming that the journalism we spend a ton, and games, and everything else we do spend a ton of money on and work really hard at through human beings... I believe it's going to be great as long as that doesn't all get misappropriated by the large language model makers.

Can we ask you about the OpenAI lawsuit? You're suing OpenAI and Microsoft for training without permission on New York Times content.

Why?

Why? Well, why did you decide to file the lawsuit?

Yeah, listen, the first thing to say is that these companies making large language models are spending hundreds of billions of dollars on compute, energy, and talent. We've seen lots of stories about that in recent days. And so we believe they should also be spending money that equates to fair value exchange on the content that they have built their models on.

So that's one. We believe the law is on our side. And by the way, not just the side of journalism. This is not just an issue for news organizations, although that is a pretty important issue to society. This is an issue for anybody who makes creative work, anyone who makes IP. And I want to say that America having a flourishing community of creators, IP makers, is foundational to our competitiveness, and really important to how we show up in the world.

This is a big, broad issue. We think the law is on our side, and we have a lawsuit, as you've just described. And we are also, you know, eager to partner with companies when the terms are right and make sense. And as we've done, we just did a partnership with Amazon, and we did that because we saw it as having sustainable, fair value exchange and giving The Times control over how its journalism and other content would be used.

So there's a thing that a lot of people — probably especially in this audience — have in their mind that wasn't really a thing yet when we did our episode in 2021. Which is this perceived anti-tech bias or anti-business bias of The New York Times. When people bring that up to you, you would say what?

First, I'm not sure a lot of people have that in mind. I'll challenge that premise. But I will say we don't. It's not a thing. The job of The New York Times is to pursue the truth wherever it may lead. And sometimes that's to uncomfortable places. And we do that job first and foremost by reporting. Reporting is we're going to unearth new facts that we think, and others think, matter in the world to a lot of people.

And it's worth saying, because I do get asked about bias all the time on any topic, it's worth saying we put an enormous amount of effort and care and money and method into trying to reduce bias in every way we can. In the process, we have a giant standards operation that really says this is an okay source or this isn't. That really says, yes, these are verifiable facts or they aren't. Every story of The New York Times is edited by at least two people. I could go on and on about all the ways we hold ourselves to account.

And on tech in particular, I want to say that many of the tech companies, the big tech companies that shape the information ecosystem, have a level of power and influence and the potential to drive profound change in people's lives in a way that governments or nations might. So we cover them accordingly. And by the way, we cover them really broadly. We did a package on AI and a view from today of what it's going to do in people's lives. And there was as much in there about all the great things AI is going to do. And I do think the more we expose people to reporting, which we do on The Daily and in lots of other formats, the more they trust us and the more they see the lengths that people like Andrew Ross Sorkin go to, to really help you understand what really is.

I mean, just to underscore the shift that's happened in the last 15 years, since the financial crisis, where tech was one industry among many and now is responsible for the majority of the market cap in this country, in this world.

Trillion dollars.

It's a big reason why people listen to Acquired. So we feel it too. On that topic of media evolution—media close to home for us—you're home with some of the biggest podcasts in the world. Yeah, how either podcasting specifically or all the different media you're doing beyond the written word, how do you think about delivering journalism today?

Yeah, I was once standing—I started the Times 12 years ago—and I was standing with Andrew Ross Sorkin in a green room. I think I was there as his handler. He must have been going to talk to an advertiser. And I grabbed him right before he walked on stage. And I said, "Don't talk about the paper. We're not just a paper company." And I would say that is how we think about and approach whatever the delivery mechanism is—if it's text, if it's video, if it's audio—we are just thinking, how do we bring our work and engage the widest possible audience?

And podcasts, the thing that you do, have just been great for the Times in doing that. We've got lots of hit shows: The Daily, The Ezra Klein Show, our new show, which is the New Right's answer to The Ezra Klein Show; "Interesting Times with Ross Douthat," and "Hard Fork," which I think is similar to you. What are those shows doing for us? One, they are deepening the engagement we have with people who already love the Times. They're making many, many, many new people love the Times. And I think, really importantly, they're helping us build a different relationship with the people we're doing this coverage and making these products for.